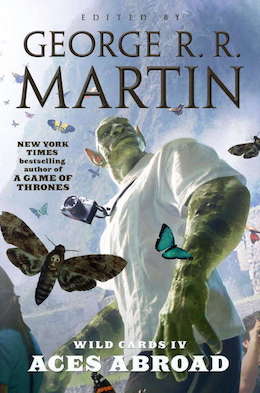

When Dr. Tod condemned the world to the wild card virus in the 1940s, he did so miles above New York City. Some of the spores floated down to the city below, but a great deal was also carried along in the upper atmosphere to other parts of world. Every so often, over the years, outbreaks occurred when the virus turned on unsuspecting human populations. While urban NYC may seem like the center of the wild card story, the virus continued to transform the planet. Other major outbreaks occurred, such as the one at Port Said in 1948, among others. It is this reality we explore in Aces Abroad, the fourth Wild Card book.

Set in the year 1987, following the dramatic conclusion of the first wild cards trilogy, a number of American aces and jokers travel the globe as part of a UN and WHO junket led by Tachyon and Senator Gregg Hartmann. Their goal is to investigate the condition of wild carders in various cultural and geographic locales. Of course, while the plight of jokers is a major concern of the group, only a few jokers are represented on the tour, as Desmond is at pains to point out. Many of the characters we meet are brand-new; others are old pals.

As was the case with the first volume in the series, Wild Cards, this book features a heavy dose of alternative history. Wild Cards gave us discreet stories spread out over decades, while here the book’s structure is not organized chronologically, but rather across geographies and cultures. Each chapter follows a POV’s story in a different international locale, from Haiti to Japan and back again. These are separated by interstitials following the unofficial “Mayor of Jokertown” Xavier Desmond, the prophetic twin Misha, and reporter Sara Morgenstern.

Desmond’s chapters are a wonderful character study as the joker leader earnestly journals his thoughts, a narrative marked by the hopelessness he feels at the world’s ills and pain as cancer ravages his body. Misha struggles for respect when other men try to control her for her prophetic dreams, while Morgenstern investigates Hartmann, not seeing the danger posed by his secret ace.

The story really gets going with Chrysalis in Haiti, snared in local politics, kidnapping, and zombi creation. The newly-introduced aces Xbalanque and Hunapu, linked as “reincarnations” of the Mayan religion’s divine twins, lead their people in revolution. In Peru, peaceful Troll plays the tourist at Machu Picchu, among native dancers, Catholic theologies, and drug cartel child kidnapping.

Heading east, in Egypt Peregrine discovers that she’s pregnant amidst religious conflict between (ancient) Egyptian religious practitioners and Islamic terrorists. She struggles with her future as a single mother, while her jealous, selfish boyfriend calls her a slut but somehow ends up as her romantic dream. The Sri Lankan diplomat Jayewardene finds himself caught up in King Kong (aka King Pongo) drama on a movie set. Cordelia winds up kidnapped in Australia, before crossing paths with Wyungare, the Australian ace who takes her on an adventure through the Dreamtime landscape. In Japan, Peregrine tracks down Fortunato, whose supersperm can apparently defeat the Pill in a single bound! He helps save Hiram from the yakuza, after Hiram gets conned in a standard (but devastating) tourist swindle.

In France, Tachyon meets his grandson—surprise! We’ll (sadly) see more of him in later books. In this chapter, Tach and Golden Boy, who have been ignoring each other the entire time, finally work together again. Lady Black, an ace protecting (or babysitting) the politicians on the trip, takes on a job looking for a politician’s wayward joker daughter in Prague. Hartmann spends most of the book reeling in Morgenstern, before Gimli kidnaps him in Berlin. The senator escapes by grabbing control of the chainsaw-massacring Mackie Messer. Finally, Georgy Polyakov amps up the Cold War spy drama, before joining ranks with Gimli. Sadly, the book ends with the death of Desmond from cancer.

Current Events, 1987-Style

Those reading Aces Abroad for the first time, and especially younger readers, will find the book a crash-course and historical review of current events in the 1980s: guerilla warfare in the jungles, Cold War tension, radical activist groups fighting for social change, secret police and village massacres, assassination attempts, and the KGB. The authors can’t get much more damning than explaining historical events like Duvalier’s dictatorship as a product of Ti-Malice’s control of Papa Doc. Desmond’s journal, especially, helps to contextualize the novel in terms of the day’s politics and social conflicts, touching on everything from joker apartheid to the Kenyan AIDs epidemic to the role of the US in toppling governments in Latin America. Some of these things I remember from my childhood, but other events I missed when they originally happened. As with Wild Cards, history fans will get a lot out of this volume.

Several chapters focus on the political revolutions so present in contemporary cultural awareness, as well as the realities of colonialism and imperialism. For example, Mambo Julia leads a rural resistance against Haiti’s urban dictator. Colonialism and revolt are major themes particularly in “Blood Rights,” with its main characters who are local indigenous aces (rather than foreign Americans). In Xbalanque and Hunapu’s world, the complex relationship between colonizer and conquered is continuously at play, with its Indian social rebellion against the Ladinos, the Spanish, and the norteamericanos. Their wild card powers allow them do what history’s real guerilla fighters could not: take back their Mayan homeland.

The theme of revolution against colonialists reappears throughout the book. Wyungare says,

We are going to drive the Europeans out of our lands…We will not need help from Europeans. The winds are rising – all around the world, just as they are here in the outback. Look at the Indian homeland that is being carved with machetes and bayonets from the American jungle. Consider Africa, Asia, every continent where revolution lives…The fires already burn, even if your people do not yet feel the heat…the whole world is aflame. All of us are burning. (322-3)

As mentioned earlier, one of the main goals of the UN/WHO tour is to assess the plight of jokers in various cultural and national contexts, which further allows the authors to investigate health, sickness, and famine across the globe. Just four years before Aces Abroad came out, Band Aid and “We Are the World” made the problem of food shortages part of pop-culture. Our American wild carders do indeed discover different ways of treating jokers, with the POVs contemplating them with various levels of insight; Desmond’s beautifully-written journal is truly our best window to the topic, though. In the first WC trilogy, we saw the American approach to disabilities, disfigurements, and chronic pain. Now, we see how jokers are treated in an international context. Hunapu’s followers, for example, are not “jokers”—rather, they are god-touched: “It was typical of the Ladinos to be so blind to the truth.” (107)

Morgenstern remarks on this alternate viewpoint of wild card disabilities: “The Mayans considered the deformed blessed by the gods…They thought the virus was a sign to return to the old ways; they didn’t think of themselves as victims. The gods had twisted their bodies and rendered them different and holy.”(73)

But Desmond argues, the “priests are all preaching the same creed—that our bodies in some sense reflect our souls, that some divine being has taken a direct hand and twisted us into these shapes…most of all, each of them is saying that jokers are different.” (130)

The Dark Side of Religion

In fact, while the topic of religion made very little appearance in the first wild card trilogy, it comes to the fore here. Several plots heavily feature religion in various ways. The wild card turns some of our POVs into the embodiments of divine figures, such as Chrysalis, the Mayan Twins, or the very Egyptian gods. There are a few religious themes that appear throughout. First, the authors explore how the Takisian virus has empowered underground religious movements and groups that had otherwise been marginalized. Second, religion is repeatedly used in the service of revolution and political uprising. Third, there is a focus on the religions of indigenous people or ancient systems. In Egypt, the Temple of the Living Gods uses its ancient artifacts to enliven a dead past; Wyungare is an aboriginal Australian who can move through the Dreamtime. Traditionally, many of these groups have been portrayed as “primitive.” For the most part, the portrayals in Aces Abroad exhibit a somewhat standard, Americanized, Western emphasis on exotic, non-Western groups. We may come across references to wild-card-hating TV evangelist Leo Barnett back in the States, but the US does not receive the same anthropological focus as these cultures, and the book doesn’t fetishize American religions as dangerous or exotic in the same fashion. Nowhere does a Native American ace kick colonizers off her land, nor is there a Shaker prophetess illustrating her visions.

At the same time, for 1988, it’s kind of a big deal for indigenous characters to have such a central role in the story. Certainly it wasn’t new, given that previous comic superteams Alpha Flight, Super Friends, and Global Guardians featured indigenous characters during the previous decade.[1] Plus, SFF had long been interested in “primitive” and mythical ways of being in the world. Still, it would be 19 years before Cleverman would give us fully-realized mainstream Australian aboriginal superheroes populating a believable politically- and culturally-based dystopia. In 1988, Aces Abroad gave us Wyungare, Cordelia’s grub-eating rescuer and Dreamtime-strolling boyfriend. Even if some of the depictions of these religions are a bit stereotypical, and the worldview filtered heavily through the lens of U.S. experience, several of the authors clearly made an effort to research and build the cultures of their characters beyond what was typical in comics at the time. The preeminence given to a (mostly) historically- and culturally-grounded international and indigenous cast, and the effort to express their voices and viewpoints in an SFF novel from the 1980s, is notable.

The book also features ambivalence about the nature of the religions it describes. In several cases, someone explicitly states that they’re using local religions to control the ignorant masses, to fool people and prop up a new power structure; in other words, it’s not real magic and religion—it’s fakery. Akabal the revolutionary tells Xbalanque, “You know, you could be very important to our fight. The mythic element, a tie to our people’s past. It would be good, very good, for us.” (94). Mambo Julia tells Chrysalis, who has found herself roped into the Haitian revolt as a representation of Madame Brigitte, the voodoo death goddess:

The chasseurs and soldats who live in the small, scattered hamlets, who cannot read and who have never seen television, who know nothing of what you call the wild card virus, they may look upon you and take heart for the deeds they must do tonight. (59)

On the other hand, there is also a strong sense that religion isn’t just a science-fiction creation of the wild card virus, as in the first trilogy’s Egyptian Mason cult. Prophecies and prophets abound: Osiris foresees Peregrine’s magic baby; Jayewardene has visions of Fortunato; Misha dreams the coming of Puppetman. At other times, it truly seems like the divine figures are real. Hunapu and Wyungare share visions of the gods, who direct their actions and give them power. Wyungare really takes Cordelia through the Dreamtime; she says, “then this truly is the Dreamtime. It isn’t some kind of shared illusion.”

What The Future Holds

Aces Abroad also sets up many of the main plots for the next few books, including the antagonists and villains. Gimli’s back, and Blaise is here. Then there’s T-Malice, the parasitic joker-ace who feeds off others and controls them by hooking into their blood stream. In this book he is the real heir of the Astronomer, a monstrous, one-sided villain ruled by self-interest and hedonism. Unfortunately, his story increases the gratuitous violence from the get-go. It makes it necessary to holler trigger warnings, including everything from torture, rape, and more snuff porn. I mean, one of his minions, Taureau, literally embodies sexual violence, killing women by f**king them to death, ripping them apart with his bull penis.

Gregg Hartmann is this trilogy’s other major mind-controlling villain—unless you’d rather I say Puppetman, the creature that dwells inside the senator and feeds off pain and suffering. I’ve never been able to buy the argument that Hartmann deserves some sympathy. Sure, he’s a Bobby Kennedy for the wild card world, working to better the plight of jokers. Or so we think. Maybe he even thinks it, too, sometimes. Yet, it makes perfect sense for Hartmann to be there amongst those who suffer, given that his inner demon revels in it. While Puppetman seems like the true monster, Hartman himself is an overly-ambitious, twisted, manipulating creep.

Our heroes are in for trouble next time.

[1] Thanks to my comics-knowledgeable friend MVH for providing some of the background here, since I know very little about comics.

Katie Rask is an assistant professor of archaeology and classics at Duquesne University. She’s excavated in Greece and Italy for over 15 years.

Glad to see a new installment in this reread!

My favorite part of Aces Abroad was Desmond’s journal. Just wonderful writing.

I’m wondering whether this volume will ever be available in Mass Market Paperback. That’s how I’ve been aquiring the Wild Cards reprints, but none of them past Joker’s Wild have made to MMP. :(

As a longtime comics reader one thing that’s notable in the WC universe is a plausible explanation for the unequal distribution of powers throughout the world — other than the unfamiliarity of comics writers with countries outside of North America and Europe. Here one can see the somewhat arbitrary path followed by the wild card virus along global jet streams and water currents but nevertheless seemingly concentrated in no country quite so much as in NYC USA. However one can also see the outsize influence that even one wild card can have in its host country especially when the right powers are combined with indigenous religious/spiritual belief and the right moment of anticolonial resistance. That’s a great point that we don’t see a Shaker wild card but I expect we will see some wild card underpinnings to our own indigenous cyclical evangelical Christian movements, especially as the forces of anti-wild card intolerance and wild card human rights both claiming Christian authority march into the scene in future books. I have seen many parallels through the years between our attitudes and fears regarding AIDS and “infectious” monsters in SFF especially zombies and vampires. T-Malice steps into this tradition.

Does this edition have more stories than the original edition? I don’t remember all of those stories from when I read it back in the 80s.

On one had, I enjoyed that we got to see some of the world outside of New York. On the other hand, it felt a bit like parts were stereotyped and researched, but not coming from lived in experience. I actually feel this a lot when reading WildCards as an adult; like it was written by some well meaning liberals, who didn’t have experience with a lot of the issues they brought up.

That said, I thought this was a good send off for Fortunato, and I liked the semi-rehabilitation of Golden Boy (who I don’t believe deserves all of the scorn that he gets in-universe). I also liked that we got to see some of the interior life of Chrysalis and Peregrine, two jokers who carry themselves pretty much as aces.

“Does this edition have more stories than the original edition? I don’t remember all of those stories from when I read it back in the 80s.”

Yes, two new stories were added, giving the POV to characters who kind of got short shrift in the original edition (i.e., Troll, Fantasy and Lady Black).

Kevin Andrew Murphy writes a the Troll/Fantasty team-up, and Carrie Vaughn writes the Lady Black story. Both were welcome additions, in my opinion.